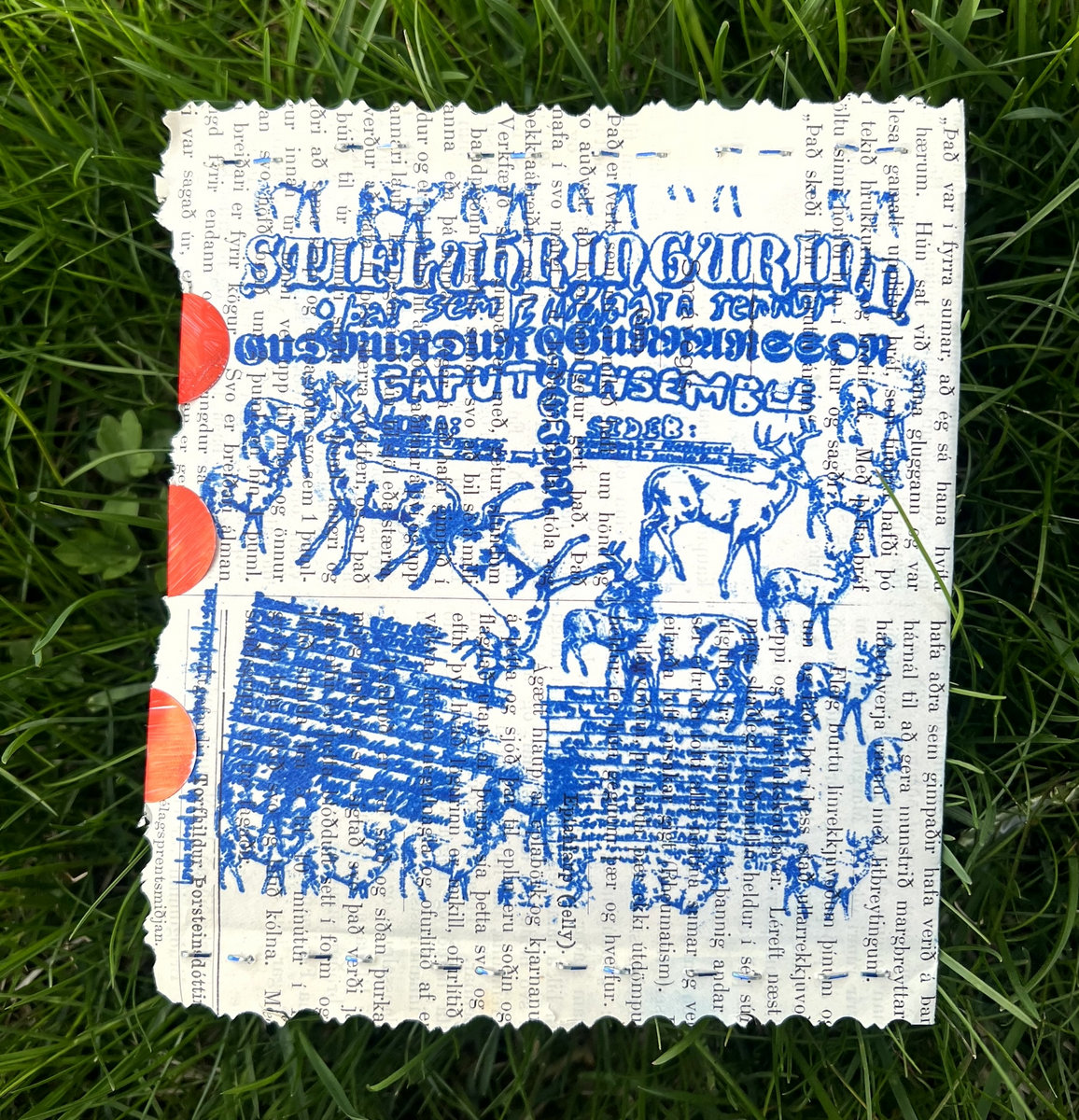

I have decided to put down some thoughts about composition on “paper.” I’ve been meaning to do this for a long time but never found a suitable occasion. Maybe it’s a rough draft of or for something. I divided my thoughts into four parts that roughly correlate with what many people supposedly associate with the parameters of sound and therefore music. But for me there are other connotations to each category as well – namely the four elements and their correlation to sound categories I worked with from 2018-ish up until very recently when things started to change again. Documenting a moment in time. Some of it has to do with my new record Stífluhringurinn directly or indirectly, but a lot of it is more general reflections on musical parameters, the way they are conventionally viewed, and what they mean to me.

1. Time

2. Pitch

3. Timbre

4. Amplitude

1.

Time

(short percussive sounds)

(Earth element)

Time is gonna mess up your mind – Prince

First, there is time. In Charles Taylor’s book, “A Secular Age,” he argues that most religions and worldviews seem to have a manifold view of time. There is linear time, perhaps different speeds. And then where time stands still, there is no time — or time is an illusion.

Making music (and other art) is the craft of making illusions. With music being so temporal, it also constantly reminds us of the passing of time, change, and the impermanence of all things. When we hear a sad song we might cry but when it’s over we may cry again and even more because the song is over.

Morton Feldman once said that he didn’t believe in music projecting grandiose ideas and ideals about the future because it is always about time passing — by the time you realize what’s happening, the moment is gone.

This is why music constantly inspires nostalgia. People use music frequently to go back in time rather than forward. Sooner or later every field and style of music is destined toward a culture of nostalgia. Again, as Feldman argued in the same interview or article or whatever it was, “I think music will always have a great past.”

Despite knowing this and music frequently reminding us about the instability of all things, changes in us, how we perceive it, etc., we are always trying to have a sense of fixedness about music as if a piece of recorded music is something concrete, repeatable, and always the same. The same goes for a score. Since it is so fleeting and never the same we tend to emphasize its fixed nature, the reality, and the absolute truth of the quality of a piece of music.

“My favorite piece of music is such and such and so and so.” But is it still my favorite when it rains? When I’ve had too much coffee or too little coffee? If I’m not feeling right, not the right speakers, not the right performance, or not the right occasion?

500 best albums of the 90s. Secular Theism. We feel there must be a fixedness – someone knows which are truly the 500 best albums of the 90s. 1790s. 1490s. 2090s. 590s.

The title of the book, “A Secular Age,” could maybe translate to “un secolo secolare” in Italian – secolo means ‘century.’ In other words, “linear time.” Linear time is secular time. Whichever other kind of time there is or might be would be whatever time is not secular.

In his book “Each Moment is the Universe,” Dainin Katagiri Roshi talks about how people are constantly decorating time, trying to hold onto it, or trying to contain it. A university degree, for instance (“See how I used my time, now it’s decorated”). A music performance can never repeat itself. Even a recording is never the same — the people listening are never the same; a musical experience cannot be repeated. We like to think the contrary that a written piece of music has some kind of solid existence. We like to contain time on a piece of paper or a computer file or something like that.

Pulse and pulses

I had the good fortune of getting to work with Pauline Oliveros, Christian Wolff, and Alvin Lucier through the Fengjastrútur Ensemble (and Hestbak) for the Tectonics Festival, as well as the Jaðarber concert series. I have taken part in performances in pieces by each of them that center around the idea of several pulses speeding up and slowing down individually. I’m not saying they are the same piece, there’s more to each of them, but what’s important is that they are all based mostly on text (and/or verbal instructions). Each of them had a beautiful and unique sound world. All were based on an idea that seems to have been in the air at a certain point.

Western notation cannot handle any of this, because there is no master pulse, no governor (no “fundamental,” but more about that later). Therefore it’s hard to develop these types of ideas with pen and paper. How can you write and structure something that goes deeper into defining which kinds of clashes of pulses, etc.?

In various Papua New Guinean musics I’ve heard what seems to me are pulses that are very musical but are not necessarily an organizational factor in the music. This and similar ideas were brought to my attention by Charles Ross, a student of Frank Denyer and Morton Feldman. As I got more and more fascinated by rhythms that weren’t governed by the conventional idea of pulse, I got more and more into faraway places until I discovered similar elements in Icelandic folk music. My venture into “otherness” went full circle; I was the other.

The 20th century came rather fast into still-medieval Iceland in the years after the 2nd World War. Some people know what I’m talking about when I tell them that for my generation, it is like being a 3rd-generation immigrant without having moved anywhere. Our old culture, which to some extent was still in living memory when I was in my 20s, seemed very far away and exotic. Less than a century earlier, people habitually ate their shoes and constantly had wet feet and woke up to the cat licking drops off their faces that were dripping down from the turf roofs. To me, this is probably at least as exotic as it is to anyone else reading this.

Long story short: I got into the idea of there being no pulse at all, no central organizing factor. That’s how most of my music works. It’s just the relationship that these moments create between one another that forms patterns of sorts.

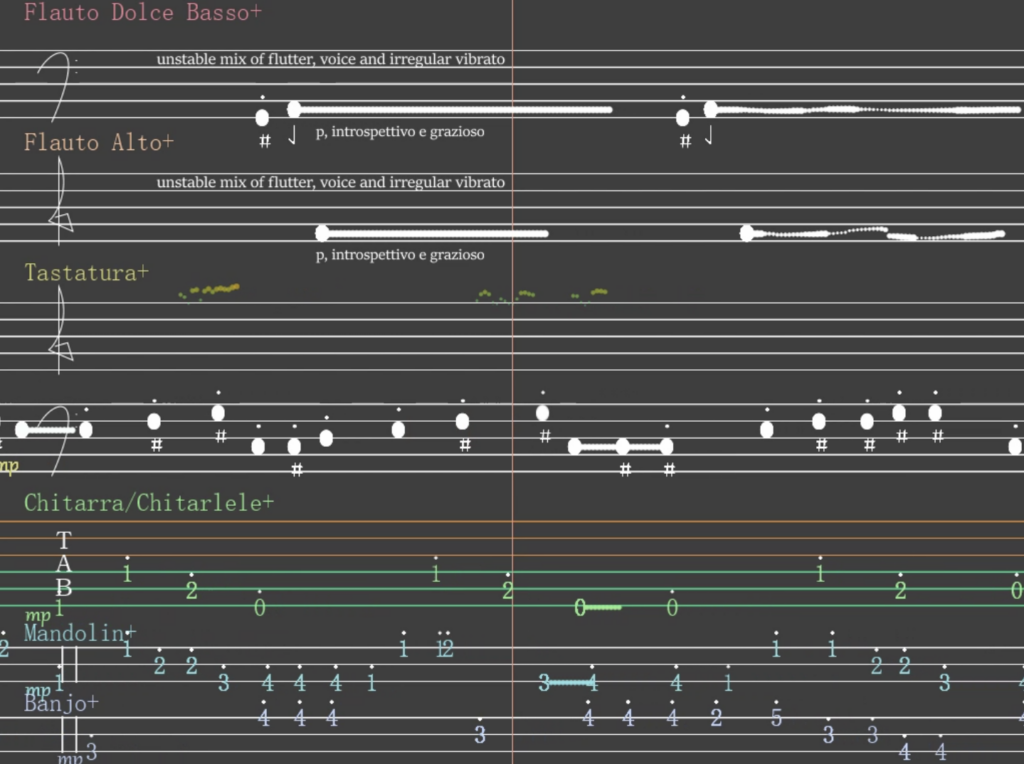

This naturally led me to discover other ways of notating music. I looked around at what people around me were doing and how I could utilize that for my own purposes. Between 2005-2015, various people in the S.L.Á.T.U.R. movement were developing their own musical languages from various types of means. Animated Notation was a big thread in all of that.

But if you don’t have the yardsticks of beats, pulses, barlines, all these things that have traditionally been viewed as the building blocks of melodies, rhythms, harmonic direction, motivic development, etc. then how do you compose? How do you generate a meaningful musical form of any kind?

Form

In the quest to make things seem more permanent, composers nowadays frequently talk about form as a parameter to be controlled and/or argued about. It has some truth in it. A truth of beauty, of proportion, etc., hopefully. Something that we can hold and control. In different continents and different languages, I’ve heard learned composers say after hearing a premiere of some new piece of music: “I didn’t quite understand the form”.

An age of form. In the 19th century, people didn’t talk about Beethoven as the superior architect of great formal constructions. They talked about the directness of the emotional expression and the unfiltered humanity of his compositions. Each age has its own definitions of what yardstick there is for superior quality: the 19th century harbored the fleeting, the 20th century loved the fixed, and the 21st century…the fixed float?

Various notions of learned form are often ways of favoring the interconnected and entangled, which make much out of little. It’s all connected somehow (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, etc.), but how are the individual parts connected in a popular piece like Handel’s Messiah? Are they actually connected?

In the keyboard toccatas of Frescobaldi, motifs and quasi-repetitions appear and disappear, but it is not as much motivic development a la Mozart/Beethoven as it is a little decorative symmetry thrown in as a decoration onto a texture driven forward by counterpoint.

Other conventional notions of form adhere to ideas such as high points or climax – build-ups of tension toward something or other. A different idea of rhythm doesn’t necessarily negate any of these ideas; what I’m trying to get at is that they are more recent than many make it seem and not the only way things have been done in the past.

I’m thinking of how the individual parts relate to one another in Bellini opera arias. Are some of these pieces a tree where everything is interconnected or are they like a bouquet of selected flowers – ordered in a way that they complement one another. Are the arias based on some motivic something? But what is their structure, say, Casta Diva? Is a motif driving the melody and the form of the song? What is?

In any music – mine or Mozart or Bellini or Frescobaldi – the smallest musical ideas inform somehow what is to come next. A musical form sprouts out of an idea. Some things can go top-down, but a lot of it is bottom-up. Sometimes these two forces – the large and the immediate – are in a constant state of negotiation. The Icelandic word for composing is semja. It also means to negotiate.

Skarstirni from 2005 was a piece that was a barebones exploration of where I wanted to go in terms of rhythm. The music was written in a proportional notation – quasi-Berio style but with barlines and boxes in order to help people place themselves relatively to one another, which is always the biggest challenge of unconventional paper notation. We used a blink-track to synchronize these lines – with nothing much ever happening right on the lines.

A year later, some of my first experiments with very similar ideas, two notes at a time for each person, became my first animated pong-style bouncing ball notation. Very raw music. Some of it had only percussive sounds.

Alvin Curran said to me when he saw this, “It was like a tree that didn’t have any leaves yet.” He was right. The leaves came later, although I told him that for 9 out of 12 months in Iceland, the trees have no leaves. For those other three, I will talk about various types of leaves, flowers, and acorns in the next three chapters.

I’ve always gone back to trimming the bushes once in a while by making music with a very limited palette. To strip everything down helps me move forward once the “decorations” start to force me to go into places unsuitable for this kind of dance, like this penultimate movement of Landvættirnar fjórar (2020-2021):

2.

Pitch

(short pitched sounds)

(Water element)

The contours do not exist in reality as strictly limited units, mechanically manipulated, but rather as types of melodic motion with fluid boundaries both in time with regard to lines, feet, and measures, and in space with regard to pitch areas or levels – Hreinn Steingrímsson

Pitch is also time, right? Frequency represents how fast a wave moves? How fast something repeats itself, really, no? But what if it doesn’t repeat itself? It’s noise, right? But noise can also have higher and lower frequencies. In order to define it, you need a starting point.

Usually when we talk about pitch, we presume a note that holds entirely stable and a wave that repeats itself in a rather stable way – that’s the conventional Western notated idea, right? But what if it doesn’t stay still? What if there is no moment in time that is definitely “the note”?

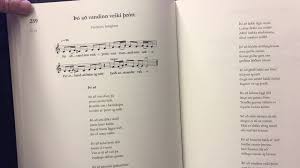

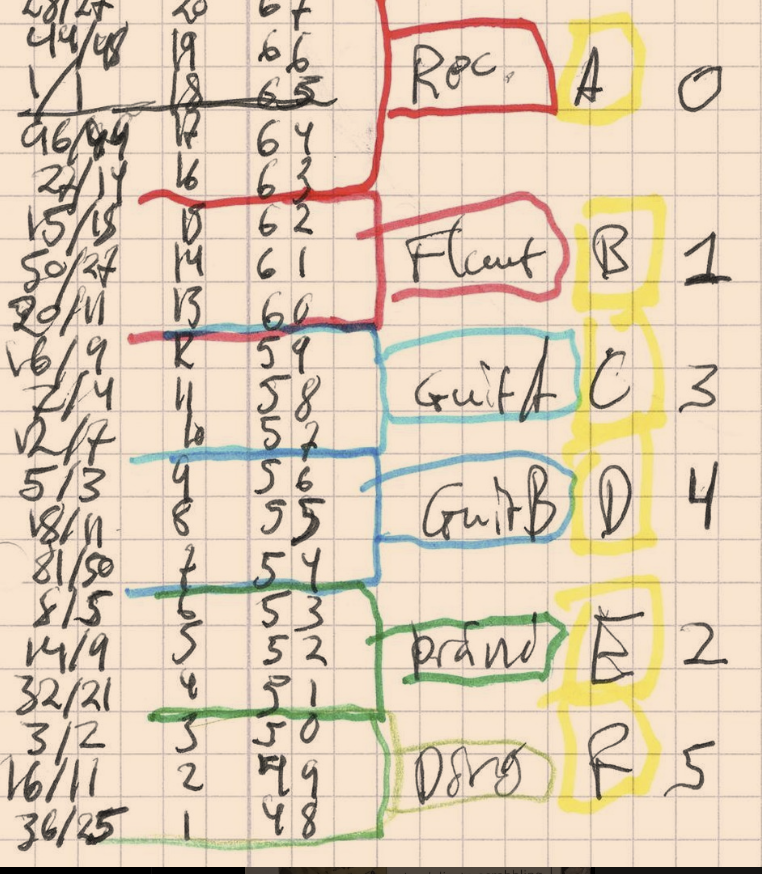

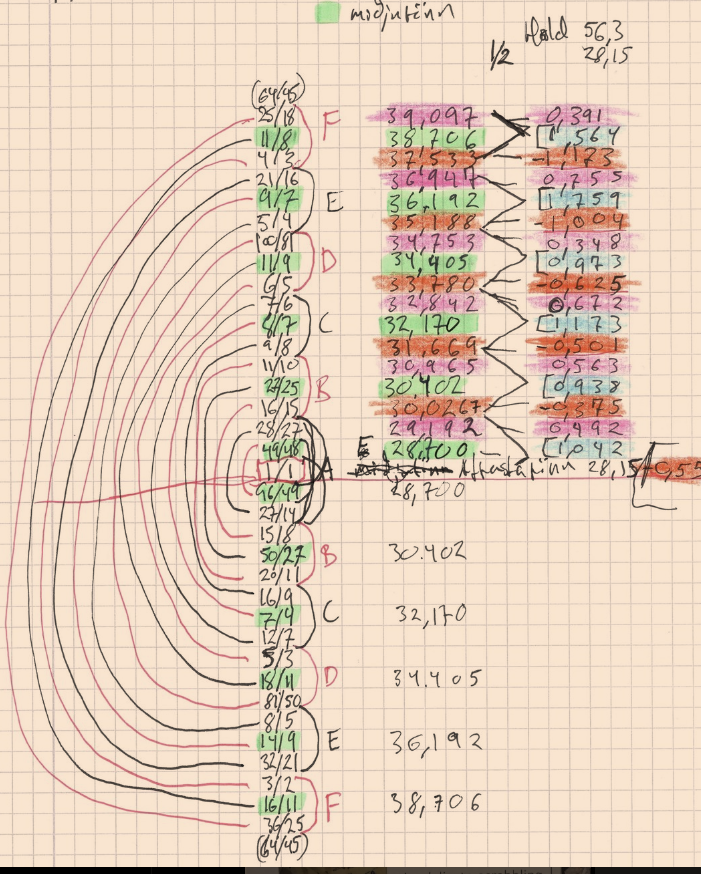

In 2008, I had the good fortune of being asked to notate 160 Icelandic folk songs for the book Segulbönd Iðunnar. These are traditional rímur melodies. I studied this music for a while and found it of enormous interest for various reasons.

In notating these Icelandic folk songs I began to realize how incredibly biased my hearing was. I became aware of how deeply cognitive and cultural conditioning shape the way we hear things. Some of the performers I was transcribing performed in a way where the pitch never settled into a single note; it was impossible to define what was the main note and what was merely decoration.

This was a deep revelation for me. My role was to pinpoint and decide on what was the main part of the musical building block at any given moment in time – what was “the note” and which was decoration.

I also needed to correct a tradition that perhaps knows no fundamental and try to ensure the performers ended roughly in the same key as they started. Needless to say, there were also issues where I had to decide whether it was a major third just a little out of tune or a microtone, etc. So I realized I was translating something from a system whose laws I didn’t know.

Hreinn Steingrímsson argues in his book Kvæðaskapur that the way the “stemmur” or core tunes are defined is more like just a contour – specific pitch classes are irrelevant or up to the performer. Of course, this was an attempt to define the “rules” in hindsight of an oral tradition. It’s an incredibly inspiring book, but hard to figure out how he came to the conclusions he did as the variability of the subjects of even just that study is enormous.

Nevertheless, it opens up a whole array of possibilities. It certainly opened up my understanding of an ingrained cultural bias that I didn’t know was there. The rímur tradition like any other has adapted the shapes and styles of musics that have arrived here later. I used to think that the more sing-songy performers were good and the ones that weren’t were bad. I didn’t understand that some of this music had totally different laws – until I did.

Even if one doesn’t believe these theories about Icelandic folk music, they have a very deep creative potential. The first thing that affected me, even before I read Kvæðaskapur, just from hearsay about its content, was the pitches of any given melody in these styles can expand and contract.

In other words, you keep the contour of the melody intact with some wiggle room for a set of built-in variations. It is still the same song even if one performer is almost mumbling in something that resembles speech, but keeps the contour and another line that spreads out and seems very melodic. Helfákn (2004) is an early venture into melodies/harmonies of small intervals:

This “dilemma” is an ongoing source of inspiration for me. Even in the world of Just intonation and the various microtonalities there is still a firm belief in a fundamental and a system that derives from that. Fixed pitches that supposedly don’t move, or the movements of the note are irrelevant somehow in the grand scheme of things because there is a “core pitch,” which is the melody.

In my compositional practice, these questions have intermingled with James Tenney’s idea of tolerance (this may have been somebody else’s idea as well, but I associate it with Tenney). This is the idea that even pre-cognitively the ear rounds off what it hears to the simplest closest interval (which should explain how we can hear a very out-of-tune major third on a typical modern piano as a major third when it is not even close, but close enough for…)

This might seem to contradict what I mentioned earlier about the absence of a fixed harmony and my role in imposing it. However, if no two notes sound at the same time, there is no fixed harmony to impose; you hear it in major even though it is a little off. It might be a combination of conditioning and pre-cognitive functioning of the ear, as Tenney argues, for instance in the Ratio Book and elsewhere.

Just intonation usually implies that you are working with very specific pitches. But with the idea of tolerance – we are looking at intervals with a broader lens. I wonder if anybody can tell the difference between an 11/9 and a 27/22 (two types of a neutral third that are not so far apart in cent). Tolerance enables the idea of translatability; the idea of a piece of music “working” in more than one tuning.

I believe that capturing intervals in their full complexity is only possible in recordings and electronic music. However, both in performances and recordings of my electronic works, my music seems to gravitate toward instability, with pitches not wanting to stay in one place.

Part of Tenney’s study I mentioned earlier suggests that longer durations are needed for one to perceive pitches more precisely. I think that’s why a lot of recent music in just intonation tends to be slow-moving. My music, on the other hand, tends to avoid low frequencies, probably because they make the harmonies too clear and obvious.

I’ve found that my desire for harmonic ambiguity is something I share with many people working with just intonation. However, my music tends to avoid settling down anywhere, so I think it is ultimately more about ambiguity than ambivalence. Additionally, the harmony seldom has time to settle in; it more often revolves around lines or clouds of tones and their interactions rather than “harmony” per se.

We usually hear classical music in a different tuning than originally intended. When we do not, we just hear one of many tunings that were around in said period. On top of that, most instruments aren’t “nailing” the tone they supposedly play (according to the combination of the notation and the tuning). With tolerance, and the translatability it creates, there must be some sort of threshold. Not just anything goes; there has to be a margin of error.

Another example of translatability specific to a musical style: I remember hearing a Gamelan piece where I had learned all the parts, but when I heard a recording of the exact same piece played on different instruments, I didn’t recognize it. Tolerance is defined by the culture that creates it.

I have made several just intonation tunings over the years. Recently I have in the back of my head a 36-tone JI, which is a rough equivalent of a 36-tone equal temperament (or the other way around). In it, every interval (except for one) is a complement of another.

However, I find that the 36-tone equal temperament is just as effective; it’s hard to nail either one. For me, the important part is that there are two notes in between C# and D. That way I can create melodies of very small intervals that then lead to contrapuntal interaction of several voices, which then lead to harmony as a result of said melodies rather than the other way around.

Usually the margin of error is tolerable for me as long as there is a proper use of the distances: they must be roughly equal (two almost equal notes between C# and D, for instance). Nobody nails it, but most people can approximate it well enough as most musical performances are approximations where the theory of tuning is very much a theory, not a practice.

A harpist often tunes the harp in Ab from a piano or a tuner, then takes a Pythagorean journey from there through octaves and fifths. They try to tune a little bit higher because through the course of an orchestral concert, then the overall pitch in the whole orchestra tends to raise. There is no such thing as a fixed point in space.

In my piece Dhorpma I Sálarró, I had my friend Halldór Úlfarsson design a set of traditional instruments that would demonstrate the just intonation version of my tuning.

My early ventures into just intonation were exploring mostly short notes, an early manifesto of sorts in the piece Horpma I from 2008 (released on record in 2011). It is a 27-tone scale, which is not a full octave scale but all the notes clutter and cluster within a major 3rd.

Again, it explores the melodies/counterpoint/harmonies like clouds of pitch relations of small intervals intending to create a new sense of proximity and distance.

3.

Timbre

(unstable long sounds)

(Wind element)

Any audible sound can be differentiated from all other sounds – Jo Kondo

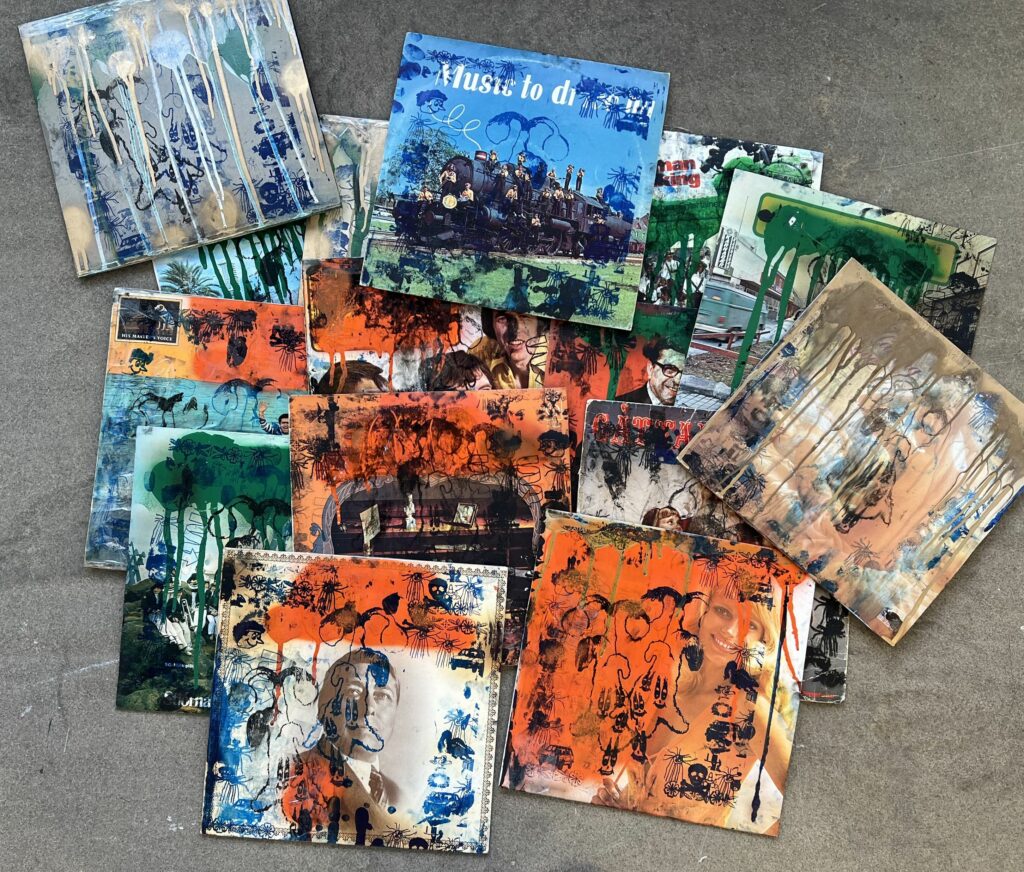

The ideas of tolerance and translatability bring to mind the subject of timbre. I used to have seven-to-nine categories of sounds instead of a 7-note diatonic scale. The nine categories included: 1) a short noise, 2) a short-pitched sound, 3) a pitched sound with a heavy accent, 4) a deep, prolonged grunting sound, 5) a longer note, 6) a sparkly high upper sound, 7) an upward glissando, 8) a downward glissando, and 9) an upward then immediately downward glissando. I used these categories as the basis for Lardipésa (2009) and subsequently all the kvartetts.

A deep, prolonged grunting sound is the same category whether it appears in the contrabass or the piccolo flute or wherever else. Its identity is defined relative to the capacity of the given sound source – it’s the inverse of harmolodics. This sets up a logic of sorts for translatability: even when arranged for entirely different instruments that respect the rhythm and the differentiation of the sound categories, the pieces become the same. If I say so, it is so.

Do these sound like the same piece?

The same logic was behind the eight octets (2014), except at that point I had paired down the sound categories to just five. By exploring these pieces in performance with different groups and instrumentation over time raises a lot of questions about the extent of the tolerance in these pieces and thereby the extent of translatability.

I can’t easily articulate conclusions, if they were any. Inversely these performances inspired me to think more deeply about timbral combinations, types of attacks, how sounds come together to form a whole where the elements are complementary to one another and yet have their own space. It’s a fine balance that’s never a given.

In writing pieces for more specific instrumentation, one has to face a lot of delicate issues as far as timbre is concerned. It is hard to separate this issue from the one of registration as these interact. How does an instrument stand out or not? Blend or not? What kind of intervals sound good in different instrumental combinations and registers? It’s always the two together: timbre and register.

I am very interested in how different instrumental combinations start belonging to each other in certain styles of music. For instance, how did the harmonica find its place in blues so easily while it’s considered an odd flavor in jazz?

Do distorted guitars call for singers and guitar solos to go way up into the high register because otherwise there is no space for them?

Does sinfonetta/solisten ensemble music need to have very dramatic high points because the brass is there and people need to find it a role?

Did Django Reinhardt and Stephan Graphelli work with a drummer-less ensemble because the whole group except for the double bass would have gotten lost inside Duke Ellington’s band? (This gets into the question of amplitude, more of that in next chapter…)

The timbre, register, and amplitude are all factors that influence which instruments people consider suitable to play together in a group. Nowadays, a composer often ends up writing for fairly random groups of instruments. That is fine, but I say that it takes 30 pieces by the same composer to see if the combination actually works. If so, how?

The same instrument can also become a totally different instrument depending on how it is used. A piano in Cuban Son/Rhumba/Salsa is not the same as in jazz. A piano in the hands of Little Richard or Fats Domino is no longer the same instrument as it is in the hands of Elton John or Billy Joel. The same pianist is rarely good at both Mozart and Franz Liszt. Yet it is the same tool.

I find that recently a lot of contemporary “classical” composers in the “avant-garde” create an instrument on top of an instrument. White noise is limitless supposedly, and so is pure light. We must limit it in order to create patterns or symbols that might have any use or meaning. Oftentimes a composer has a palette of sounds and scales they find work well with this or that instrument. The same goes for extended techniques.

For example, let’s compare Helmut Lachenmann’s Mouvement with Iubiri by Horațiu Rǎdulescu, both of which involve various types of extended instrumental techniques but hardly any of them are overlapping. With Lachenmann and his descendants, the approach often feels like the techniques are designed to negate the inherent nature of the instruments i.e. air sounds, noise, percussive sounds coming out of instruments that usually play lots of long notes.

In the case of Rǎdulescu, there is a palette of sonorities where everything rings, resonates, and sounds. Rǎdulescu affirms the nature of those instruments by stretching and exploiting their weaknesses.

The modern-day composer bound by notation is always bound by people who can read his notation i.e. there always needs to be an “educated” individual on each instrument. This might be one of the reasons why instruments that have gone out of fashion in popular genres often find a new home in the so called “avant-garde.” It seems like once you no longer hear an instrument on the radio, you see it in a new music ensemble.

The most recent example is the electric guitar, although the same thing happened with the saxophone, the accordion, the vibraphone, various muted trumpets (especially the ever popular harmon mute with its wah-wah effect, not much on the radio anymore but huge in the concert hall, especially since 1980 or so).

As Peter Ablinger pointed out, “avant-garde” is perhaps a misnomer for a specific field of contemporary classical music. It is a conservative style in reality and that’s okay! And yet, one composer can bring out an entirely different palette out of the same instruments. But like any genre or style of music, there is a fixture, fixtures, and rather fixed forms of variations.

I must say I like to experiment with different instrumentation but my preference is to repeatedly write for the same sets of instruments. My taste for the wind element has strengthened over time and it has increasingly become more prominent in my music.

For me, the wind element has many shades of meaning, some more literal than others. When my piece Landvættirnar fjórar was performed in Iceland, the only movement out of 12 that a lot of people seem to be able to make a direct association to a singular place is this one:

Icelandic audiences usually associate that movement with the area around Hafnarfjall (windy). It’s a very noticeable element in Iceland in general but particularly near Hafnarfjall.

4.

Amplitude

(long, pitched sounds)

(Fire element)

If we lose our limitations, we lose half our qualities – Charlie Chaplin

Some of the aforementioned sound categories also relate to amplitude as in articulation, ADSR, the type of attack or non-attack. How does a note start? How does a note end?

As a composer, one of the greatest musical challenges I have had to face is trying to get a feeling of how instruments combine both timbrally and dynamically. I didn’t have a knack for this kind of thing in the beginning so I’ve thought about it a lot. For instance, the kvartetts don’t work unless all the instruments have a very similar dynamic range (or similar enough). The more I’ve thought about this topic, I find that I’m not alone.

Early pieces like Horpma I and Lardipésa were multi-tracked and initially existed only as recordings. This allowed me to experiment extensively with the balance. With Horpma I, me and Jesper Pedersen sat for hours and hours trying to make it all “work.”

Horpma featured a collection of re-tuned kotos, harps, harpsichords, guitars, clavichords – all plucked strings. The attacks of these instruments are so incredibly different that we had to extensively shape the sounds using gates, compressors, and whatnot to ensure all the instruments could be heard. This was important not only harmonically but also to enunciate the rhythm of the whole spiel.

This process taught me a lot about how ‘plucked string instruments’ — or ‘saiten instrumente’ — can have vastly different amplitude shapes and dynamic curves. While this might be obvious to many, it sparked my interest in researching various combinations of attacks, especially with percussion. There are so many different types of attacks.

The symphony orchestra is a vehicle that has evolved over time for “indoor” and “outdoor” instruments to blend together. However, in a string quartet, there are inherent dynamic issues due to the differences in amplitude between the cello and the other strings. Many of the techniques used in writing for string quartets are probably intended to compensate for these differences (i.e. all the ridiculous octave doublings in the traditional repertoire).

In Bach’s time, brass and percussion were outdoor instruments – really, they were military instruments hired by the military on the military budget for special occasions. Bass drums, snare drums, and cymbals were referred to as “The Turkish Set” in Beethoven’s time, which refers to the fact that they were adopted from Turkish military music. Loud, synchronized brass bands were meant to intimidate the enemy. Nowadays, you go to a small rock club and might find a “Turkish Set” playing to us through a P.A. system almost as loud as a jet plane.

In pieces like Leyfðu hjólinu (2017), I started incorporating built-in laptop/tablet speakers to deliver electronic sounds to lurk in the background. I started using small loudspeakers beginning with Einvaldsóður.

A lot of my recent pieces, including Laberico Narabida and Stífluhringurinn, use my collection of “belt” guitar amps with the smallest possible speakers (3″ or less) when I put up the wires for the pieces. Whenever I’ve purchased any of these speakers, the clerk in the store usually gives me a speech about how there isn’t that much power in that thing (“Just so you know”). At the premiere of Laberico Narabida, some people complained about how loud it was in the tiny avant-garde venue even though it was much softer than the average jazz concert.

Loudness is therefore rather relative. It is about blending the elements and it’s always, inseparably about time, rhythm, and form.

For me, the greatest luxury is to hear sounds – acoustic or electric, amplified or not – blend through individual sources in the same room. Every room, player, and instrument is different; they can never sound the same. For me, this is the most “expensive” and “expansive” way of listening to music.

This way, you also get the most tolerable listening experiences to the same music, as variety is naturally built into the process—you can’t control it fully, no matter how hard you try. It is best to listen to music with speakers that has been delicately and accurately crafted to sound good through speakers.

As much as I enjoy fine music through stereo speakers, I prefer to have this experience at home, ideally with the right tea. Apart from the cinema, I do not want to pay money to hear music coming from loud stereo speakers.

The problem with the P.A. or the big loudspeaker is that it is “perfect” – it covers the entire dynamic range. An instrument, however, is more like a “bad” speaker: quirky, with limited frequency range, louder in some registers, softer in others, and with sound that varies directionally across different frequencies.

Music comes into being through limitations, not endless possibilities. To create is to limit, not open up. If you want to be open, do nothing.

In his search for a music with neither grids nor straight lines, Icelandic composer Guðmundur Steinn Gunnarsson incorporates digital dynamic screen scores or animated notation to express his inability to adapt to the convenient society. His interest in Icelandic folksong has fueled his belief in life without barlines or equal distances and no-grid approach to music.

Leave a Reply